“On The Fly” Part Two: Disintegration

(The second of four parts. Previous part.)

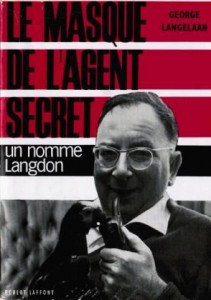

George Langelaan’s life story might seem the stuff of fiction. Born in 1908, he served as a spy during World War II and received plastic surgery in order to protect his identity during an operation in France. After parachuting into occupied territory, he was captured by the enemy, imprisoned, and condemned to death. Before the sentence could be carried out, however, he escaped from the camp where he was being held and returned to England to take part in the Normandy landings. He was a friend of occultist and provocateur Aleister Crowley, who once confided to him that Crowley was himself a spy and that the sinking of the Lusitania was the result of his urging the Germans to demonstrate their superior willpower to the Americans. As well as science fiction and horror, Langelaan also wrote spy fiction and several memoirs concerning his time as an intelligence agent. Later in life he wrote for film and television, on occasion for Alfred Hitchcock, and died in 1972.

George Langelaan’s life story might seem the stuff of fiction. Born in 1908, he served as a spy during World War II and received plastic surgery in order to protect his identity during an operation in France. After parachuting into occupied territory, he was captured by the enemy, imprisoned, and condemned to death. Before the sentence could be carried out, however, he escaped from the camp where he was being held and returned to England to take part in the Normandy landings. He was a friend of occultist and provocateur Aleister Crowley, who once confided to him that Crowley was himself a spy and that the sinking of the Lusitania was the result of his urging the Germans to demonstrate their superior willpower to the Americans. As well as science fiction and horror, Langelaan also wrote spy fiction and several memoirs concerning his time as an intelligence agent. Later in life he wrote for film and television, on occasion for Alfred Hitchcock, and died in 1972.

But first, “The Fly”, which received Playboy’s award for Best Fiction of 1957 and was reprinted in The Year’s Greatest Science Fiction and Fantasy anthology—the first of many reprintings. A film adaptation came out the following year, starring Vincent Price in a script by James Clavell, who would later go on to write The Great Escape and To Sir, With Love. The film won a Hugo Award for Best Dramatic Presentation and was a commercial as well as critical success, spawning two sequels, Return of the Fly (1959) and Curse of the Fly (1965).

At first glance it is hard to see why “The Fly” was such an instant hit. What separates it from the other matter transmitter stories published in the 1950s? After all, in briefest possible terms, its synopsis seems simple enough: a scientist invents d-mat but makes a mistake and turns himself into a freak that must be destroyed, almost note for note the same as “The Man without a Body”. It too could almostbe a condensed form of Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein—condensed in the sense that monster and creator are one and the same being—but “The Fly” is no simple warning about the over-reaching of scientific ambitions. In Frankenstein we are encouraged to damn the scientist and feel compassion for his creation, while in “The Fly” the scientist isn’t damned until he’s been transformed, and even then he remains an object of sympathy. Similarly, the death of Victor Frankenstein’s monster is as ambiguous as its birth, whereas in all existing versions of “The Fly” the inventor of d-mat is tragically but decisively destroyed by the woman he loves.

Looking at the plot of the original story in more detail reveals many subtle but compelling nuances. André Delambre is a brilliant scientist who, working alone and in secret, has invented a system of “disintegrator-reintegrators” that allows him to move physical objects from one place to another without traversing the space between. After some teething troubles—an ashtray that arrives reversed, the family cat disappearing but never reappearing—he perfects the machine and tries it on himself, not knowing that an ordinary housefly has entered the disintegrator with him. When he arrives at the reintegrator end of the machine, his head and one arm have been switched with the insect’s matching body parts.

Looking at the plot of the original story in more detail reveals many subtle but compelling nuances. André Delambre is a brilliant scientist who, working alone and in secret, has invented a system of “disintegrator-reintegrators” that allows him to move physical objects from one place to another without traversing the space between. After some teething troubles—an ashtray that arrives reversed, the family cat disappearing but never reappearing—he perfects the machine and tries it on himself, not knowing that an ordinary housefly has entered the disintegrator with him. When he arrives at the reintegrator end of the machine, his head and one arm have been switched with the insect’s matching body parts.

Enlisting the help of his wife Helene, and communicating entirely by typewriter, André attempts to locate the mutated fly, intending to return both of them to normal, without success. She begs him to go through the machine again in the hope of reversing the error, but that only makes things worse: now he has gained aspects of the missing cat, its “essence” haunting the machine in some unguessed way. Lacking hope of restoration and fearing how his invention might be misused, André decides that he must destroy all evidence of his failure, first by smashing his invention beyond repair, then by convincing Helene to crush his upper body to a bloody mess under a hydraulic press. When this is done, Helene telephones her brother-in-law François to tell him that she has killed André, and to ask him to call the police.

The story of André’s tragic carelessness is indeed little different to that of Professor Dummkopf in “The Man without a Body”, only with a wayward fly derailing the experiment instead of a prematurely discharged battery. Both André and Dummkopf promise technological revolutions that will “completely change life as we had known it so far”. They both offer rational-sounding explanations of their breakthroughs, although André’s are conveyed in the briefest possible terms, coming as they do via his wife’s written testimony and François’s first-person account, thus reducing the burden of scientific proof on the narration. Both inventors muddle through early trials in order to build up to their first human subject: themselves. Simple errors result in severe physical mutations that end their working lives and see their inventions forgotten. The tragedy in each of their stories is that they made a mistake, not, as in Frankenstein, that they committed crimes against nature.

What makes “The Fly” stand out among stories of this time is not its plot, but the context in which it is situated. The one thing Helene withholds from her confession is her reason for killing André, and it’s here, with a bloodthirsty crime and a mystery concerning Helene’s apparent lack of motive, where the story begins. As such “The Fly” sets up a very different narrative to the one that unfolds: the solving of a murder and its connection to a mysterious fly, as opposed to a morality tale concerning the perils of modern science. What the reader receives is the explication of a suicide—two suicides, ultimately, as Helene is unable to live with the guilt of what she has done. François shares her confession with the inspector in charge of the case, who insists that Helene must have been mad. They agree that the manuscript should be destroyed. However, at the close of the story François reveals that he actually found the fly his brother and sister-in-law had been looking for—a fly with one white head and arm—and interred it next to André’s grave, as the reader is left supposing it (at least partly André) might have wished.

What makes “The Fly” stand out among stories of this time is not its plot, but the context in which it is situated. The one thing Helene withholds from her confession is her reason for killing André, and it’s here, with a bloodthirsty crime and a mystery concerning Helene’s apparent lack of motive, where the story begins. As such “The Fly” sets up a very different narrative to the one that unfolds: the solving of a murder and its connection to a mysterious fly, as opposed to a morality tale concerning the perils of modern science. What the reader receives is the explication of a suicide—two suicides, ultimately, as Helene is unable to live with the guilt of what she has done. François shares her confession with the inspector in charge of the case, who insists that Helene must have been mad. They agree that the manuscript should be destroyed. However, at the close of the story François reveals that he actually found the fly his brother and sister-in-law had been looking for—a fly with one white head and arm—and interred it next to André’s grave, as the reader is left supposing it (at least partly André) might have wished.

This framing narrative gives “The Fly” considerable emotional heft in its original form. François’s post facto narration lacks any kind of generic self-awareness or mockery, establishing a tone of dread that “The Man without a Body” or “Rabbits on the Moon” are entirely lacking, and which Langelaan is careful to maintain. There is not one moment of release from the terrible situation, not one hope that is’t dashed—for the reader knows where all of André and Helene’s best efforts will lead them. No amount of domestic bliss or affluence can save them or their son Henri from horror and brutality. André’s intentions were good, but there is no upside to bodily corruption. Not even love can undo the wrong that has been done to him.

The use of a hydraulic press—a machine with a brutal name: the “steam-hammer”—is critical, not just as a means of ridding the world of the evidence of André’s accident, but also of emphasizing that the true threat of the story is neither André himself nor or the creature he becomes, but technology itself.

The use of a hydraulic press—a machine with a brutal name: the “steam-hammer”—is critical, not just as a means of ridding the world of the evidence of André’s accident, but also of emphasizing that the true threat of the story is neither André himself nor or the creature he becomes, but technology itself.

But what is actually threatened? Physical transformation, yes: the twisting of André’s form is a detail dwelled upon in the short story. The vivid description of the raising of the steam-hammer to reveal his remains is just the first of many gruesome revelations, becoming steadily stranger and more disturbing until André’s final shape is unveiled.

However, something much more hideous than any mere mutation of the body is artfully signaled in François’s opening line:

“Telephones and telephone bells have always made me uneasy.”

The opening two and half paragraphs of “The Fly” are devoted not to Helene, not to André or André’s machine, not even to André’s murder—not to anything, in fact, for which the story might be consciously remembered. Instead, Langelaan devotes considerable wordage to describing François’s struggle with the “unease” or even “panic” he feels at the “downright intrusion” of telephones in his work and at home: a sense that “in spite of doors and walls, some unknown person is coming into the room” and invading his personal space.

The leap from the telephone to matter transmitter—a device that would allow someone to literally step from room to room—is seamlessly explicated during the course of the story via the enlistment of radio and television as metaphors. This technology is not something completely new, Langelaan subtly suggests: its antecedents are with us already, their effects are already being felt, and in the future the invasion of personal space that François fears is only going to get much worse.

(Next in Part Three: Destination)